Artlecture Facebook

Artlecture Facebook

Artlecture Twitter

Artlecture Blog

Artlecture Post

Artlecture Band

Artlecture Main

Last week, I have introduced the anchorite saint Julian of Norwich and have briefly explored a section of her famous text, The Revelations of Divine Love. The hermit saint who h...

|

HIGHLIGHT

|

Last week, I have

introduced the anchorite saint Julian of Norwich and have briefly explored a

section of her famous text, The Revelations of Divine Love. The

hermit saint who had spent most of her days within the confines of her cell in

Norwich shared her out-of-the-body experience in writing, which transcended the

age and reached our present selves.

It is always the minute

things which are often overlooked that comes to mind as one sits and ponders

about life. As a self-identified medievalist that walks the planes of this

earth in 2021, a small fragmentary piece of ivory, holstered in an exhibition

hall in one of the biggest museums in London came to my mind this week.

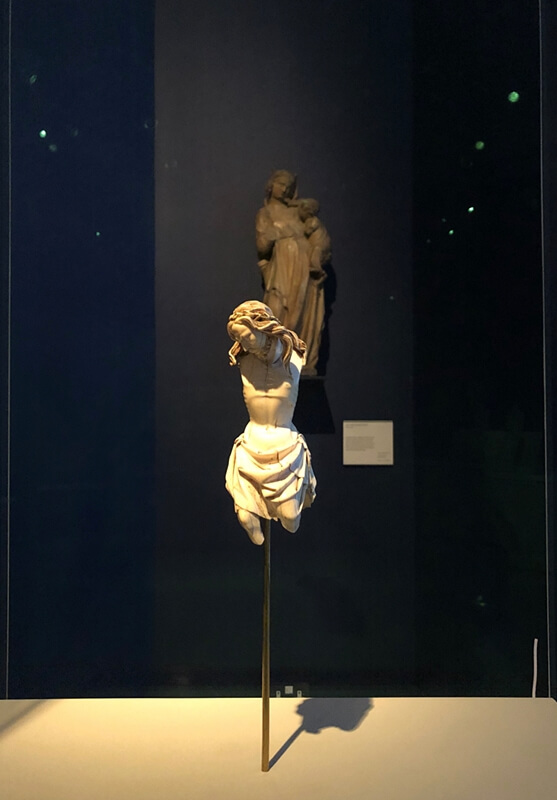

Figure 1. Giovanni

Pisano, The Crucified Christ, c. 1280s. Victoria and Albert Museum,

London.

Source : Author’s own.

In the Room 9 of the

Medieval and Renaissance Gallery in the Victoria and Albert Museum, there lies

a small piece of ivory, resting in a case that is perhaps far too big for its

diminutive size. (Fig. 1) It is a fragmentary remains of a statuette of the Crucified

Christ, made out of ivory with traces of gilding in the air and colouring

in the loincloth. Here, Christ is shown at the point of death, with his eyes

closed and his head turned to one side; his mouth is slightly agape and the

veining of the ivory creates several gashes on his left cheek, emphasising his

suffering. (Fig. 2) The work depicts the iconography known as the Man of

Sorrows, a popular motif to be depicted in ivory. His long hair is divided into

three distinctive cascading locks and falls onto each of his shoulders and down

the back. (Fig. 3) His beard appears to have been trimmed short, encasing the

entirely of his jaw. The corpus of Christ, carved fully in the round, is now

missing its arms and legs below the knees. The two gaping holes on its

shoulders indicates that the arms would have been formed from separate ivory

fragments, designed to be slotted into them. (Figs. 4 and 5) The legs has been

roughly broken off. The figure carries an almost “Baroque”

sense of rotating figural form: the upper part of the body twists to its right,

whereas the lower half turns to its left. The figure gently twines around its

axis, and this serpentine form creates a sense of emotional drama, vividly

manifesting the the moment in the salvation narrative in which the slackened

body of Christ, slumps heavily with the burden of sin and suffering.

Figure 2. Giovanni Pisano, The Crucified Christ, c.

1280s. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Source : Courtesy of V&A Museum, London.

The fragmentary ivory

crucifix, which has been attributed to Giovanni Pisano,[1]

kindles three different concerns: firstly, the choice of the material, the

religious motif used, and the meaning that it seeks to communicate, when the

two former points are taken together into consideration. The following

paragraphs will endeavour to explore the material property of the ivory as can

be read from the object, the significant role that it plays in unveiling the

theological significance of the depicted Christ on the crucifix. The broader

question of the role of material as an agency in creating meaning in works of

art will be considered.

Figure 3. A Detail of Giovanni Pisano, The Crucified

Christ, c. 1280s. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Source : Courtesy of V&A Museum, London.

/

Figure 4. A Detail of Giovanni Pisano, The Crucified

Christ, c. 1280s. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Source : Courtesy of V&A Museum, London.

/

Figure 5. A Detail of Giovanni Pisano, The Crucified

Christ, c. 1280s. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Source : Courtesy of V&A Museum, London.

High naturalism is the

most prominent formal aspect of the work on multiple levels. The alternating

technique of high and low relief, while it demonstrates the sculptor’s

technical skills, presents us with a highly naturalised depiction of the

Christ. The directional flow of the long hair, marked by long, linear carving

is starkly contrasted by the short coiling hair of the beard. The ribs are

merely indicated by subtle low relief carving while the finely pronounced frown

lines on the forehead are incised carefully to create the impression of the

suffering Christ. The loincloth shows the rippling textures of the ivory which

has been carved on varying degrees of depth. Such effects, while affirming the

technically advanced skills of the sculptor, are also achieved due to the

physical properties of ivory. Valued and appreciated for its unique structural

properties, ivories are made out of dentine cells in formation of enamel that

takes a honeycomb appearance with the development of mineral crystals.[2]

This gives them a tensile strength, making it suitable for long-lasting,

detailed carving, as evident from the fine tendrils of hair and the

loosely-falling clothes of the object. An oily substance within the cavities of

the interlacing patterns in the tusk that helps to reduce the brittleness and

that gives a smooth finish, which can be enhanced with polishing. This gives a

clean beauty and soft feel to the work akin to human skin, adding to the sense

of naturalism.

The work, while it may

have been opalescently white, appears to have been discoloured, and yellowed.

This again, could be explained by one of ivories’ physical

properties, as they are prone to change over time, especially when brought into

frequent contact with human skin, oils and perspiration that makes the creamy

white colour to darken. The work, given its small scale (approximately 15 cm in

height) is likely to have been used as a portable crucifix that one would have

held in his hands for recitation prayers. The discolouration is especially

evident around the torso, whose features have been yellowed and darkened,

perhaps testifying that there would have been frequent contact with moist

palms.

The lack of polychromy

present emphasises the smooth, even surface of ivory. The work bears

resemblance to human bone fragments, by which symbolic associations could be

made. Ivory, as a material, is imbued with theological significance, as found

by several biblical references from the Old Testament. Most famously, King Solomon allegedly ‘made a great throne of ivory and

overlaid it with pure gold’, which associates ivory

with luxury, power and glory — a belief that was prevalent in the Middle Ages.[3]

A stark contrast is provided in the example of King Ahab, a corrupt king of the

Northern Israel, made a house of ivory, which downgrades the morality of the

material as a representation of vanity and superficiality.[4]

One further reference could be found from the Book of Amos that states, ‘and the houses of ivory shall perish’, which adds a prophetic,

apocalyptic dimension to the ideas surrounding the material ivory,

prognosticating that wealth and vanity will come to an end.[5]

Such theological significance that attest to the vanity of life, emphasises the

perils of an attachment to transient worldly pleasures. This object, however,

is laced with a sense of paradox. The material, which is complicated by its

symbolic biblical associations addressing the futility of vanity, is paired

with the iconography of the Crucifix, the symbol of eternal salvation that

embodies God’s atonement of the sin and the triumph

over the finality of life. The ivory, in this sense, works in relation with the

subject depicted, serving as a warning to its beholder to embrace an attitude

of contemptus Mundi — the contempt of the world.[6]

Taking both the

properties and the symbolic values of the ivory into account, the material

object that we might have in front of us generates a sense of uncanniness of

having the miniature mimetic representation of the broken holy body — the

humanised God — materialised in one’s hands. Duality of powers is conveyed in

the work. The emotive iconography and the use of ivory coexist together to send

across a powerful ecclesiastical dialogue of problem and solution: the

condemned futile human life met by the God’s extended hand of salvation. The

idea of holding the symbol of salvation — the eternal afterlife, a concept far

removed from one’s physical presence during lifetime, triggers an emotional

response and perhaps, enhances the sense of desperation and the longing for

salvation that its original beholders would have had whilst praying using the

crucifix. This is echoed by Daniel

Miller’s argument who propounds that materiality has the power to elevate

objects from being ‘mere things as artefacts’ to those that ‘transcend the

dualism of subjects and objects’.[7]

The beholder would have been prompted to recognise his own mortality while

becoming more aware of the materialised immaterial divine being in his hand. It

is this tactility of the material object that gives greater power to the

message, which makes the use of ivory highly significant and integral in

communicating with the beholder. The nature of this message remains common in

late medieval works of art and this crucifix finds its place within the larger

group of tangible devotional objects. Being able to hold the object in the very

moment of worship, allows greater sense of connection with the deity during

worship, intensifying the desire to reach salvation through acts of devotion.

This materialisation of grasping what is seemingly intangible, which ivory

offers, would have made the work highly powerful medium in its own right.

Contrary to the

original beholders however, the modern beholders are presented with the

fragmentary remains of the statuette — it is a literal translation of the

broken form the the broken body of Christ. This prompts one further question: how

does the materiality of the work change its agency over the modern beholders?

The material agency becomes more charged as the broken form makes the viewers

more aware of both the jagged texture and the smooth exterior surface. The

textural juxtaposition confronts the viewer with material quality of the work.

Reflecting on the idea of materialisation of the immaterial, the tactility of

the object, provided by the ivory, is the essential element that allows the

work to exercise its agency — when forms have the power to cause effects — on

its original owner.[8]

This is an object whose intangible concept has been materialised to give it a

tactile quality that ensures a physical contact with the owner. The signs of

age and utility evident from the discolouration further challenges the

kinaesthetic curiosity of the modern beholders. Recalling Miller’s

anthropological ideas of how objects could act as the “mirror” of human

activities by bearing these marks that display the preoccupations and the lives

of its original beholder, the present state of the ivory testifies to its own

history, giving the material a greater agency as the signifier of the object

history.[9]

The socio-historical

context, in which the work may find itself changes. The current society no longer

operates within a system reliant on organised religion as compared to the

thirteenth century social models and the object has been removed from its

original location — whether it would have been an Italian church, a domestic

space or the pocket of the original intended beholder — to a acrylic vitrine in

the Victoria and Albert Museum amongst other medieval objects (stained glass,

altarpieces, other ivories alike) from the continental Europe. (Fig. 6) It is a

marked transition and transportation from a religious sacred space into an

educational secular space, which doubles as a cultural depository of artefacts.

The surrounding space, the nature of the viewer, the social beliefs have all

changed, yet the material is the one unifying, lasting factor that continues to

exist in the same form. It bears the history of the object as signs and carries

the theological, historical, and conceptual significance: adding a great weight

to the ivory.

Figure 6. Room 9 of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Source : Author’s own.

Pisano’s choice to use

ivory in depicting this broken corpus allows greater naturalism and strengthens

the religious message conveyed due to its physical properties and traditional

associations with Christian faith. The uncanny resemblance of ivory with human

bones serves as a physical and actual reminder of mortality at hand, which is

answered by the christological iconography of Man of Sorrows. The

materialisation of the concept that the subject embodies, adds a newfound

dimension of tactility, which elevates immateriality to materiality that allows

the work to communicate its universal message of God’s salvation on a more

direct and assertive level. On this account, the work has an agency on the

owner; however, it is the material - the ivory - that inaugurates the meanings,

raising the status of the work from a mere repository of meanings to the object

where its meanings are integrated with its material nature. It is also the

material — ivory — that gives a greater sense of weight, of monumentality to

the object.

[1]

Attributed by John Pope-Hennessy in 1965.

J.

Pope-Hennessy, “An ivory by Giovanni Pisano” Victoria

and Albert Museum Bulletin. Vol. 1, no. 3, (July

1965), pp. 9-16.

[2] A

MacGregor, Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn: The Technology of Skeletal

Materials Since the Roman Period (Beckenham, 1985) pp. 14-16.

[3] 1

Kings x,18 and 2 Chronicles ix, 17

[4] 1

Kings xxii, 39.

[5] Amos

iii, 15.

[6]

Paul Williamson and Glyn Davies, Medieval Ivory Carvings: 1200-1550 Part I,

(V&A, 2014), p. 472.

[7] Daniel Miller, Materiality, (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2005), p. 3.

[8] op.

cit. p. 11.

[9] ibid.,

pp. 17-20.

☆Donation:

Sarah J Yoon

I read History of Art as an undergraduate at Oxford University and studied Medieval Studies for masters at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Presently, I am working as a researcher for a private art collector that specifically collects antiquities in Seoul. My primary research interest lies within the late medieval European visual and material culture, touching on the semantic relationship between images and text, historicity, and reinterpretation of medieval art history in light of contemporary critical theories

Vernissage "Madness and Practice" Liz Dawson + Lucy Teasdale

WHAT DREAMS MAY COME: Sabine Carlson, Irene Christensen, Stephanie Lempress, & Sarah Riley

Ideas of Africa. Portraiture and Political Imagination

HOLIDAY MADNESS

Mateusz Choróbski, P.OST

CONTEMPORARY VENICE 2025 - 17th EDITION

Suzanne Moxhay: Thresholds

The Dancer on the Net, Cookies in Suspension

Welcome to T/C Latvia : Latvian pavilion at Venice Biennale

James Lee Byars, 1932–1997

James Turrell - Aftershock

Hrair Sarkissian: The Other Side of Silence

Bruce Nauman. Neons Corridors Rooms

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You

Jitish Kallat: Order Of Magnitude

Chun Kwang Young: Times Reimagined

Gillian Wearing: Wearing Masks

*Art&Project can be registered directly after signing up anyone.

*It will be all registered on Google and other web portals after posting.

**Please click the link(add an event) on the top or contact us email If you want to advertise your project on the main page.

☆Donation: https://www.paypal.com/paypalme2/artlecture